The Malaise. The Paradox of Scarcity in an Abundant World

Forty years ago, waiters dreamed of their children becoming lawyers. Today, lawyers have nightmares about their children ending up as waiters.

The original (Spanish) version of this post can be found here.

This article is part of Plutonomics, a series aimed at shedding light on what may be the greatest challenge of modern society: the collapse of the 20th-century way of life and the emergence of a new, yet-to-be-illuminated reality. The goal of these articles is to provide a theoretical foundation for a generalist book I am working on, where I won’t be able to explore this topic in such detail. To receive future installments in your inbox, don’t forget to subscribe!

10 Predictions About What Is Already Happening (Coming Soon)

Plutonomics. Toward a New Science of Meeting Human Needs.

In the first part of this series, we explored how, since the rise of the internet, humans have increasingly met their needs through abundant goods. Because economics does not concern itself with such goods—except when their production requires scarce resources—our perception is that the economy is shrinking. This is the answer to what economists have called the productivity puzzle, the enigma of productivity. There are more and more activities that no longer take place within the traditional economy but in a different sphere: the plutonomy.

And yet, one paradox remains unresolved: How is it that, at the most abundant moment in history, we have such a pressing sense of insecurity? How is it possible that, even as we cover more needs with abundant goods, this widespread discomfort has emerged? If people are increasingly enjoying goods at no cost, why do they still feel a sense of scarcity?

Capital in the Age of Plutonomy

Abundant goods produced in a decentralized manner require far less capital than private goods. When mobile phones replaced 20 or 30 physical devices at once, when banks replaced branches with mobile apps, and when streaming platforms took over from DVD rental stores, the companies operating in these industries no longer needed to invest in offices or large-scale manufacturing infrastructure. With every replacement of a material, scarce good by an immaterial, abundant one, fewer investments became necessary.

As a result, private investment in productive capital has dropped by 80% over the past 40 years. This figure applies to publicly traded companies in the U.S., but it is not hard to imagine that the trend extends to other countries as well.

As various authors have extensively explained—Schumpeter, Minsky, and Arrighi among them— when capital cannot find enough opportunities in the productive economy, it either becomes idle, gets financialized (as happened with the subprime bubble up until 2008), or, as is happening now, turns speculative.

This is why, in 2025, two-thirds of all global wealth is concentrated in real estate (1)(2). In other words, most of what we consider “wealth” is not embedded in the productive economy, it does not generate new goods or services but remains "locked" in real estate assets. Even more concerning, the majority of wealth growth since the year 2000 has not come from the creation of new forms of value but from the appreciation of those real estate assets.

Some might argue that it doesn’t really matter how the economy generates value, as long as that growth is later redistributed. They could claim that what we’ve been witnessing in recent decades is a redistribution problem driven by ideological factors. In other words, that what truly matters is how wealth is shared, not who creates it.

But the economy is not merely a system of production and distribution—it is, fundamentally, a moral system. That’s why we don’t allocate resources randomly or distribute them arbitrarily. We reward those who generate wealth and well-being for society because we believe this creates a virtuous cycle—one that fosters more value, more wealth, and greater prosperity.

And this holds true across all ideologies. The differences between the left and the right revolve around who creates value—whether it's entrepreneurs or workers, investors or caregivers—but everyone agrees that those who generate the most well-being should be rewarded.

What’s happening now is that the moral mechanisms that govern compensation and value allocation have been corrupted. We reward unproductive actors while overlooking those who are innovating and creating wealth and well-being in the 21st century. No ideology can construct a coherent narrative about the value of landlords in today's world because it is blatantly clear that they produce none.

This is why recognizing the phenomenon of plutonomy is so urgent: to rebuild a moral framework for value distribution that is not just fair—I would settle for one that is merely functional. And we cannot establish a system for attributing value while ignoring the growing number of goods that are being created outside the traditional economy.

There’s still another question to answer. If the economy as we once knew it—the one we still picture, with its factories producing goods and its service industries—has shrunk to a bare minimum, and if a significant part of what we now call the economy is nothing more than a global Monopoly game that produces nothing… then why do assets keep appreciating? Why doesn’t everyone just move to the countryside or to smaller cities, causing real estate values to drop?

The New Natural Resources

There is a basic survival instinct that drives humans to cluster around the resources that sustain life. This behavior can be observed from the earliest settlements along the Euphrates to the present day. That is why, during the Industrial Age, populations migrated from rural areas, where fewer resources were produced, to industrial centers.

Urban design followed this pattern, giving rise to cities of various sizes, each specializing in one or more industries, attracting populations through economies of scale.

But abundant goods are not produced in factories: they emerge from social interaction. In this sense, cities have become the factories of value in the 21st century. They are the new industrial hubs—or, more accurately, the new natural resources of nations. With their universities, creative classes, cultural diversity, and convergence of capital, skilled labor, and entrepreneurs, cities are the new oil. And those who want to succeed in the plutonomy must be where the largest number of people—and the most intelligent ones are, just as, in the past, success in the economy required proximity to factories.

At the same time, the concentration of population forces the massive service sectors of advanced economies to be where people are, further accelerating urban convergence.

As a result, the past few decades have seen a massive population shift toward large—very large—cities. The global urban population has risen from 37.3% in 1975 to 55% in 2018, with a growing trend projected to reach 66% by 2050.

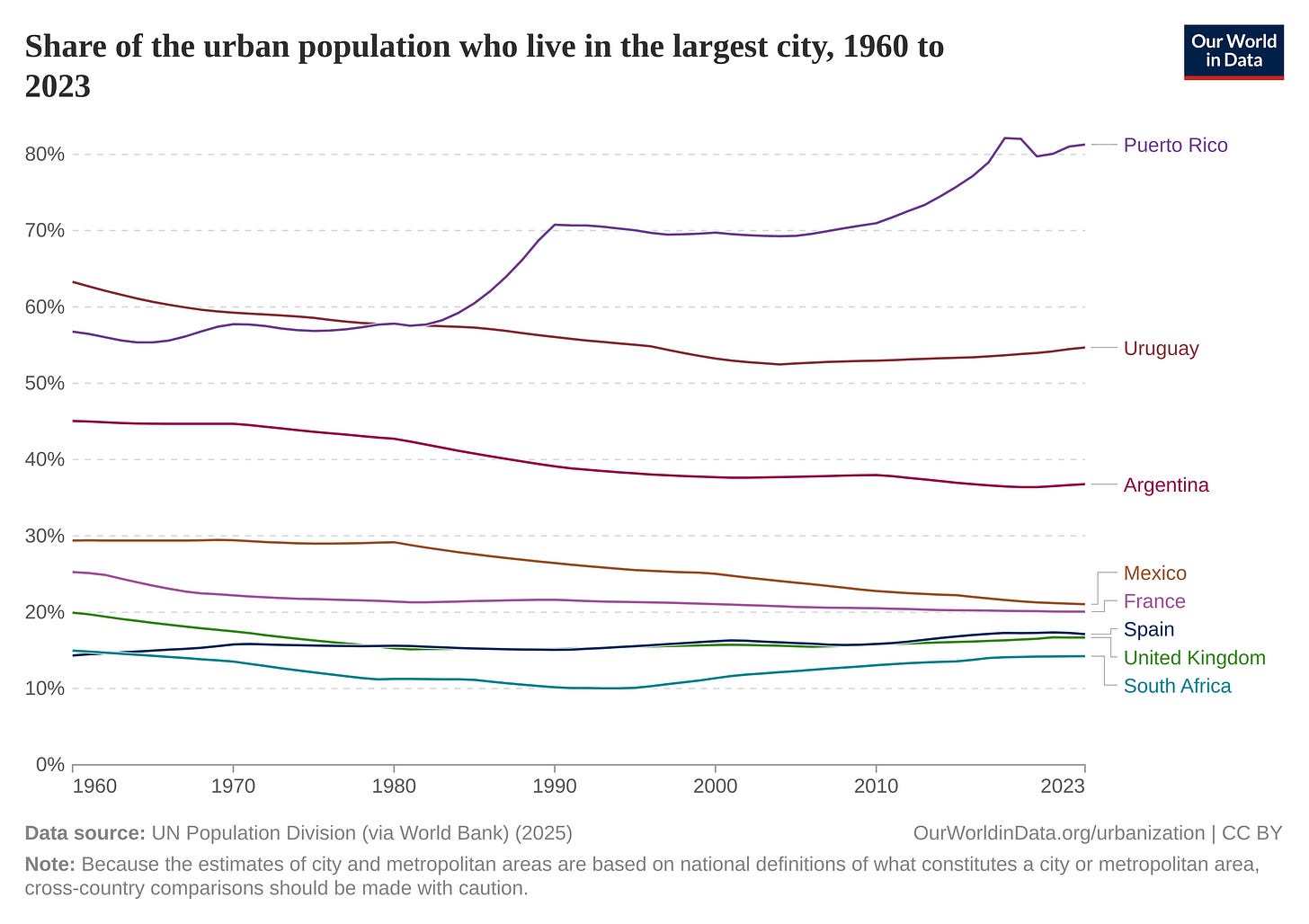

Source: Our world in data

And while the economy of the second half of the 20th century led to the rise of medium and large-sized cities, today's trend toward urban concentration is bringing most of the population into a much smaller number of hubs. In each country, an increasingly large share of people is clustering around a single dominant city.

Just as capital has historically flowed toward valuable natural resources to secure returns, it is now concentrating in the natural resources of the 21st century: cities. The difference is that, in the past, this was a productive capital—extracting oil or coal required major investments—whereas today, capital cannot directly invest in these new resources because abundant goods are not investable. As we have seen, they are produced and consumed in a decentralized manner.

This is why we are witnessing a new cycle in which capital is not just becoming more speculative but increasingly rentier. It does not generate value, it captures it. In cities, capital seeks assets that provide near-guaranteed cash flows, and it finds them in the only sectors that still appear to offer a secure stream of rents: real estate and infrastructure.

This explains why, since 1985, housing prices have multiplied by 12 in London, by 6 in New York, by 7 in Paris, and by 4 in Madrid and Barcelona.

A crucial metric that could serve as a proxy for understanding how much of economic life is being consumed by housing costs is the percentage of lifetime income spent on rent first and then on homeownership. For many social groups, that percentage has likely increased tenfold in recent years.

Beyond housing, infrastructure—transportation networks, energy, communications, and other essential services—has become a refuge for capital, because it is also capable of capturing the wealth produced in cities in the form of rents.

It is important to remember that neither infrastructure nor housing operates as a conventional market. On the contrary, they function based on state-granted entitlements (such as concessions or occupancy permits). In other words, they are monopolies that allow those who already hold the capital to control the prices or even be the sole providers of essential services in a given area.

What we are witnessing is a total distortion of the productive system we once built—one that still lingers in the collective imagination. In the 20th century, capital enabled the creation of new goods and services, which, as a byproduct, generated stable jobs that allowed people to afford housing.

Today, the world has turned upside down: value is increasingly created outside the traditional economy. Meanwhile, good jobs are becoming scarce, and instead of facilitating homeownership, a growing share of wages is funneled into the hands of a capital class that no longer contributes but merely extends its hand to extract the value created by others.

We are edging closer to a neofeudal system in which people, in order to sustain themselves, must surrender a substantial portion of their income to the owners of the places where they need to live. Meanwhile, capital behaves as an extractive mechanism that siphons the plutonomic value produced in the cities. It is a rentier capital. (If you're interested in this topic, I explained here why real estate investment behaves just like Bitcoin.)

The fact that there has been no serious discussion about limiting these monopolistic and extractive practices can only be explained by the web of vested interests surrounding the extraordinary returns that capital continues to receive.

The malaise

Thanks to the fact that real estate investment is counted as gross capital formation and rental income contributes to GDP, economic growth and investment figures can still be manipulated to look as growth. But what cannot be manipulated is people's lived experience.

Just as abundant goods reduce the need for capital, their expansion also naturally leads to a decline in employment. This is why, in nearly every utopian vision of a future where humanity has overcome material scarcity, no one works. This is why Keynes predicted 100 years ago that we would be working just 15 hours a week, and why Rifkin and many others described the end of work as an almost imminent phenomenon 40 years ago.

And yet, work never truly disappears—nor will it ever—as long as the space left by the decline of scarce goods is filled by an ever-increasing cost of housing and infrastructure. In fact, in the absence of the stable, well-paying jobs that the economy provided four decades ago, people today are forced to accept underemployment—low-paying, precarious jobs that fail to match their skills and capabilities.

Today, 25% of university graduates in Europe and 40% in the U.S. are overqualified for their jobs. Worse yet, they see no future,neither for themselves nor for their children. If 40 years ago, waiters dreamed of their children becoming lawyers, today, lawyers have nightmares about their children ending up as waiters.

At the same time, leaving the cities is not an option because wealth is now generated within them. This is how we arrive at the paradox of a world of abundance where people remain trapped in an economy of scarcity. An economy that is shrinking.

Without a proper analysis that examines the problem from outside the traditional economy rather than within it, governments across the political spectrum are tempted to give life support to the old productive system—hoping to revive it. This is the reasoning behind policies promoting reindustrialization or increased investment. But it won’t work.

No amount of public investment will bring back economic growth because no reindustrialization plan can stop this transition toward abundant goods. This shift is intrinsic to human nature and the way knowledge spreads. In the years ahead, we will only see the traditional economy deflate further, giving way to plutonomy, as more and more sectors make the leap from one system to the other.

And as long as we fail to explain this phenomenon to ourselves, people will continue to perceive that certain social groups are taking everything: the increasingly scarce good jobs in the economy and all the advantages of living in an abundant world. When they talk about wokism, this is what they are referring to.

The path forward requires us to recognize this phenomenon, study it—hopefully, with departments of plutonomy in universities—and accept that the economy will never again be the central pillar of everything. The industrial era was a historical moment that brought us to where we are today, and we owe it gratitude for levels of well-being that would have been unimaginable just three generations ago, but it is coming to an end.

And the world urgently needs two transformations:

First, as we have seen, we must put an end to the perverse mechanism by which capital strategically positions itself in cities to extract value it does not create. Because it is immoral and because it is a death sentence for the economy itself, as it encourages parasitic behaviors. Technically, this would be very simple—and no, we don’t need to build public housing to achieve it—it would be enough to require a license to put a property up for rent.

Second, the time has come to confront, once and for all, if not the end of work, at least a drastic reduction of the workweek to four days, or perhaps even less.

Because it makes no sense for an activity—the economy—that no longer satisfies all our needs, but rather an increasingly smaller fraction of them, to continue occupying 100% of our lives.

As we move into a world that is less and less defined by the economy, we must adjust our time to allow everyone the opportunity to participate in the plutonomy.

And we must begin explaining this shift to all those confused and frustrated people who need a coherent interpretation of the world—one that gives them a new place in society beyond work and bank account balances.

The truth is that millions of people already find greater satisfaction in the activities they engage in within the plutonomy than in the economy. Most of us already have an unpaid—or poorly paid—activity that we feel produces more value than what we do within the economy, because it does.

A 21st-century agenda must recognize this reality and embrace it. And we must rethink the moral systems we inherited from the 20th century to adapt them to a new era.

Photo by Cullan Smith on Unsplash