On the nature of goods (Plutonomics)

The original (Spanish) version of this post can be found here.

This article is part of Plutonomics, a series aimed at shedding light on what may be the greatest challenge of modern society: the collapse of the 20th-century way of life and the emergence of a new, yet-to-be-illuminated reality. The goal of these articles is to provide a theoretical foundation for a generalist book I am working on, where I won’t be able to explore this topic in such detail. To receive future installments in your inbox, don’t forget to subscribe!

10 Predictions About What Is Already Happening (Coming Soon)

Plutonomics. Toward a New Science of Meeting Human Needs.

A large number of the comments I have received following the publication of this article relate to the nature of goods. This was to be expected, as the existing classifications in economic theory today have several significant gaps that lead to much greater misunderstandings about the world than one might think.

It is worth taking a few minutes to shed some light on the topic.

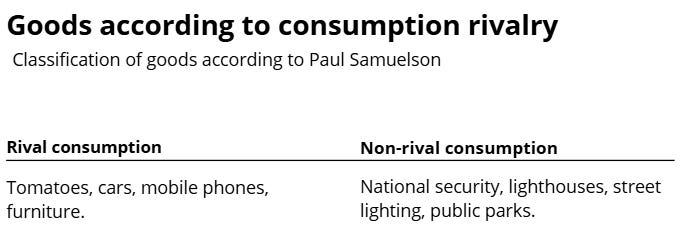

Paul Samuelson popularized in the 1950s the first division of goods into two categories based on the rivalry of consumption. He called them private consumption goods and collective consumption goods.

A good is rival if the consumption by one individual reduces the ability of others to consume it. For example, when one person eats a slice of pizza, it becomes impossible for another person to consume that same slice. On the other hand, many people can simultaneously consume a recipe without one person's consumption reducing the availability of the good for another. Therefore, the pizza slice is a rival good, whereas recipes are not.

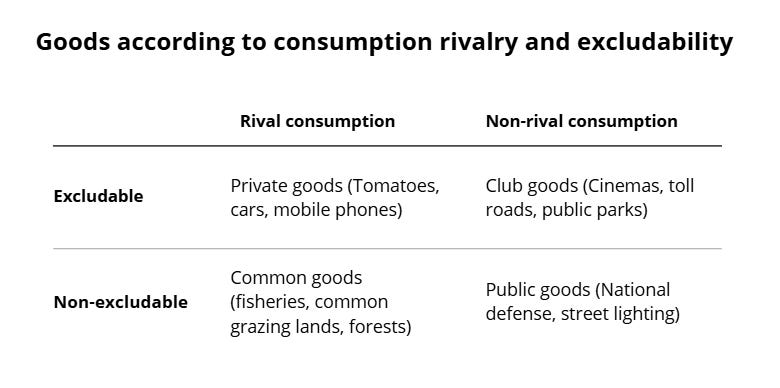

Years later, Richard Musgrave expanded this classification to include a new property, which involved determining whether a third party could be excluded from its consumption. A good was considered excludable, Musgrave said, if a "fence could be put around it" to prevent someone from consuming it. For example, public parks would be excludable goods because they can be fenced to prevent unauthorized access, while street lighting would be a non-excludable good: once installed, it would be impossible to prevent anyone from using it.

By crossing the property of consumption rivalry with excludability, a classification emerged with four types of goods: private, public, common, and club.

Private goods: those whose consumption is rival and excludable, such as clothing, food, or cars.

Public goods: those whose consumption is non-rival and non-excludable, such as national defense, lighthouse light, or GPS signal.

Club goods: those whose consumption is non-rival but, since they are excludable, can be traded, such as cinemas, roads, or public parks. Although these goods were originally public, they allowed "putting a fence around" to limit consumption.

Common goods: those whose consumption is rival (i.e., they are depleted by consumption) but non-excludable, such as fishery resources or forests.

From these properties, Elinor and Vincent Ostrom proposed some variations in 1977 that added nuances to this classification, which I will not delve into because they incorporated what I consider the original sin of this framework, which is the "excludability" of goods.

For two reasons:

The first is that whether a good is excludable or not does not emanate from a property of the good itself, but from the technology and culture available in a community to make that good excludable. For example, television was a public good (non-rival, non-excludable) until the technology existed that allowed signals to be encrypted and decrypted. Since that technology was invented, one should say that television is now a club good (non-rival, excludable).

Similarly, if we consider an urban park a club good (non-rival, excludable), we should consider the same for a pasture, because they are essentially the same thing. However, most authors consider pastures common goods (rival, non-excludable) because we are used to urban parks being fenced and pastures not. But it is perfectly possible and the technology is available to enclose both. Not fencing pastures is a cultural—or economic—decision, if you prefer.

It could also happen that one community decides to "fence" a good, and another does not. For example, 8% of roads in Germany have tolls, but only 0.1% in the U.S. do. Are roads a club good (non-rival, excludable) or a public good (non-rival, non-excludable)?

Secondly, goods considered club goods are actually private goods, only we are not correctly attending to the nature of the good. Cinema tickets do not sell the content of the movie, which, in its audiovisual nature, would be a public good (non-rival, non-excludable), but rather the occupation of space inside the cinema, the seat, in other words. And the seat is a scarce good; it is a private good (rival, excludable).

What Musgrave was actually asking was whether a good is marketable. Goods whose consumption is non-rival cannot be bought or sold as such unless one can prevent others from accessing them without having acquired them. But whether a good is marketable or not depends, as we have seen, on the cultural, technological, and economic practices of the community using the good, not on the good itself. This is why this property does not help us understand the nature of goods and only adds confusion to the debate.

Understanding goods in the 21st century

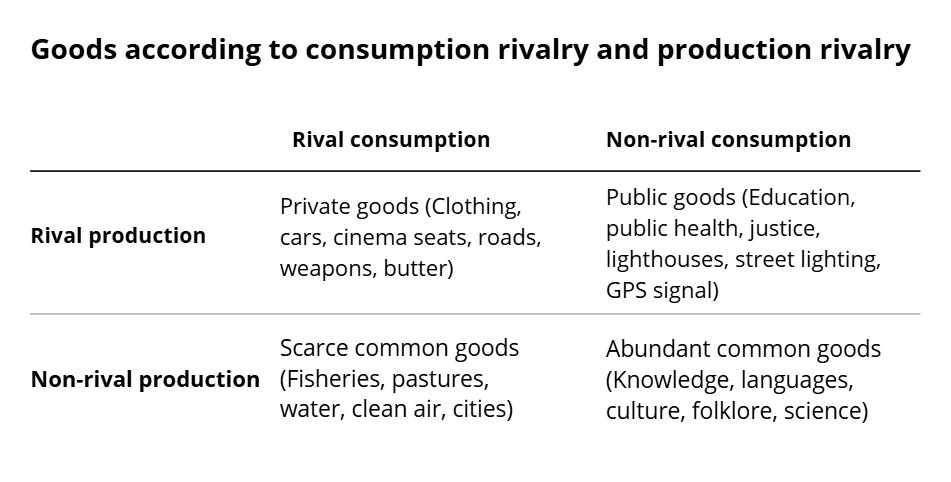

To get to a functional classification of goods for the times of plutonomy, we should maintain two properties. First, the property that helps us understand how goods are consumed, which was Samuelson's initial approach. Then, another that helps us understand how they are produced.

We can carry this idea of rivalry in consumption to production and distinguish goods based on whether their production is rival or not. The production of a good is rival when it forces the diversion of resources from the production of another good. If I make bombs, I cannot make butter with the same resources.

When the consumption of a good is non-rival but its production is, as in the case of a coastal lighthouse, we will have public goods. These are goods that require the intervention of an entity outside the market, but one capable of organizing production and making decisions about the scarce resources applied to its provision.

The production of a good is non-rival when it does not deplete resources from the production of another good. Languages, for example, do not require anyone to divert resources from another activity to create, evolve, or maintain them. While one person speaks, without doing anything beyond conversation, they are contributing to the maintenance and diffusion of their culture and language. Languages, knowledge, or cooking recipes are examples of goods that are non-rival both in production and consumption, and we will call them abundant common goods.

Resources that are available in nature without human intervention would be considered non-rival production goods, while they are rival in consumption. These would be scarce common goods.

Dual goods

Some activities produce multiple goods at once: in their particular application, they are a private good, but as a whole, they produce a public good. For example, medicine, when provided as a service, is a private good, but it produces an additional public good, which is public health. Public health allows societies to prosper more because it reduces the spread of diseases, improves the quality of life, and increases economic productivity by keeping more people healthy and able to work. Although the provision mechanism is the same (hospitals, doctors, nurses, health centers), two goods are produced at the same time: one is the curing of diseases, and the other is maintaining public health. The same happens with education.

Private initiative, copyright, and abundant common goods

Markets cannot, by themselves, produce abundant common goods. Not only for the well-documented reasons in academic literature about the non-rivalry of consumption but also because the production of these goods is non-rival.

However, by using intellectual and industrial property laws, patents, encryption technologies, and other cultural mechanisms designed to exclude people from consuming them, some instances of these abundant common goods can indeed be exchanged in markets. For example, music—the chords, rhythms, musical genres, melodies—is an abundant common good, but through copyright, a market agent can record a song and charge for it whenever it is played.

If this is possible, it is not because the song is not an abundant common good, but because a cultural mechanism external to the good itself is forcing it to behave like a private good (rival in both consumption and production). This was Musgrave’s excludability.

But if those rules did not exist, songs would be made as languages are, through the continuous mixing and transformation that happens in society when they are used. And, in fact, although in that particular instance the song behaves artificially like a private good, it still contributes and remains part of that other abundant common good, which is the musical heritage.

This happens not only with music but also with technology or software, where this forced excludability makes a part of these goods, their concrete manifestations, behave as if they were private goods against their nature. That is, market agents are producing some instances of abundant common goods.

This can lead to confusion about the idea that knowledge is not truly an abundant common good, but if we pay attention to the nature of its own dynamics of production and diffusion, we will observe the opposite. Even while specific representations of that knowledge might be protected, the knowledge itself continues to mutate and expand. This is precisely what is happening with artificial intelligence and machine learning: while some concrete models might be subject to restrictions, the field as a whole advances relentlessly, fueled by the ongoing recombination and diffusion of the underlying knowledge.

As knowledge moves from more copyright-protected areas, like music or books, to others that do not have such artificial protections, like software or mathematics, it becomes clearer that all forms of knowledge are abundant common goods.