Work and Twinkies

The original (Spanish) version of this article can be found here.

There was a time when all calories were considered equal. If you asked the consensus among nutritionists, they would tell you that it didn’t matter what you ate—as long as your calorie intake was lower than your energy expenditure.

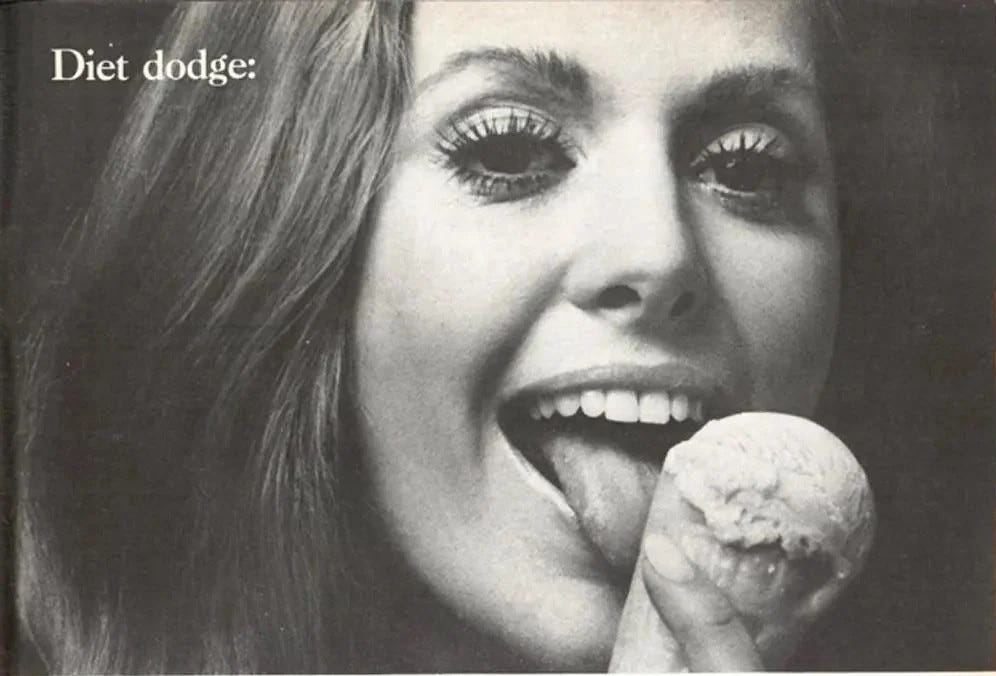

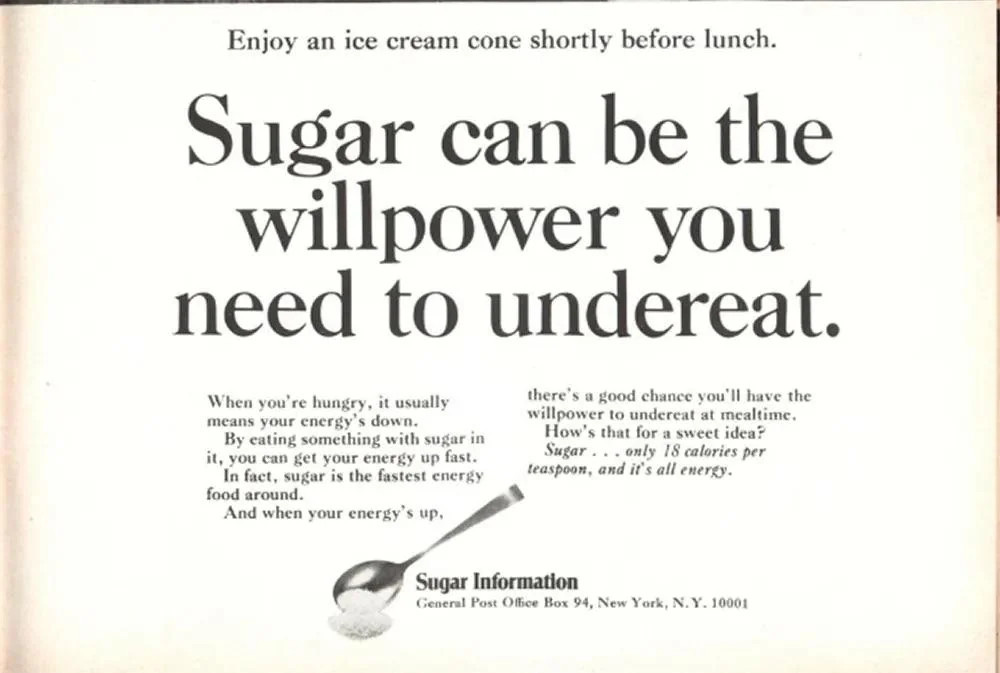

Some say that theory was invented by Coca-Cola to keep selling sugar water. Either way, for many years, the common belief was that it didn’t matter whether your 2,000 daily calories came from donuts and beer or from spinach. If anything, spinach had a slight advantage: since it had fewer calories per gram, you could fill up (or get bored) more often on spinach than on ice cream for the same calorie intake—but that was it.

Today, we know nothing could be further from the truth. The quality of food, and the speed and way in which our bodies transform it into energy, are far more important for health and nutrition than the mere number of calories.

If you gorge yourself on Twinkies, your body gets a literal glucose jolt that sends your hormones into a frenzy. But if you consume the same number of calories in spinach, your body will likely take hours to process them, digest less than half, and ultimately expel a significant portion.

That’s why, in nutrition, other indicators have been developed—like the glycemic index—to explain the effects of different foods on the body.

Something very similar is happening with work. There was a moment, toward the end of the 20th century, when it seemed like all jobs were going to be good jobs: well-paid factory jobs, long-term company jobs where you could start in the mailroom and retire 40 years later as sales director, retail jobs where everyone knew your name. Jobs that offered dignity, meaning, and participation to those who did them.

Of course, it was never quite like that. Just walk into an old bar and meet the lifeless stares—like zombies—of waiters with 30 or 40 years of service behind them. Like calories, not all jobs were ever good jobs.

But around the year 2000, the expectation was that there would be many, many good jobs, and that’s not what happened. On the contrary, most jobs created since 2008 have nothing to do with that illusion: they are ultra-processed labor. Not only are they poorly paid and offer little room for advancement, but it’s increasingly common for big companies to manage their workforce like machines, organized around strict, tech-driven processes. Just like ultra-processed foods, these “jobs” may look like 20th-century employment on the surface, but they’re full of additives, preservatives, and trans fats. As a result, these jobs become dehumanized, and many people feel like a meaningless cog in an anonymous machine.

And the problem is that the entire cultural scaffolding of the 20th century was built on the idea that there would be good jobs. A happy life was a life where you could feel fulfilled—or at least valued—through the work to which we dedicate such a large portion of our existence.

In the 20th century, work was a vehicle for social participation. Today, we’re seeing the rise of a new social class, which a brilliant author once called the unnecessariat: a workforce shuffled between jobs that require nothing of what makes us human, filled by people who are instantly replaceable, who don’t belong, who barely even exist as people at work. Confusing the myth of 20th-century employment with what these people actually do is like confusing spinach with Twinkies.

We urgently need new words and new ways to distinguish good work from this other category. Some studies are starting to focus on job quality, and they show that fewer than half of all jobs qualify as good jobs.

We millennials are trapped in this reality. We grew up with the expectation that we’d find happiness in our “career paths,” but only a tiny fraction of our generation seems to have actually found it.

And—no surprise—the correlation between having a good job and feeling like you have a good life is extremely high. Seventy-two percent of people with a good job say they have a good life, compared to just 32% of those with a bad job.

In other words, today, there’s no such thing as a good life without good work. It’s the opposite of what we’re told every day, as if we should be grateful just to have any job. “A calorie is a calorie,” they used to say. “Don’t complain—you’ve got a job,” they say now.

Will the good-job paradigm return? I doubt it. The global economic trend is moving the other way: toward a small number of excellent jobs, a large number of poor ones, and more and more capital funneled into sectors that create no employment—like housing.

So where do we start, then, to invent a new ideal of the good life? I believe the real challenge of the 21st century is to finally, once and for all, confront the great taboo that’s haunted economics and society for the past 30 years; the utopia that John Maynard Keynes proposed a hundred years ago: the end of work.

Or, more precisely: the end of mandatory employment for social participation. Not because technology will inevitably cause mass unemployment (that doesn’t seem to be happening—in fact, people keep working whatever they can just to pay rent), but because, as a society, we need to grow up and move beyond this juvenile phase of history into something richer, more vibrant, and more meaningful—where you don’t have to sacrifice your life at the grindstone just to survive.

And yes, being part of society should still mean contributing in a real, responsible, and meaningful way: by creating, learning, generating value, connecting, caring—all the things humans are far better at than repeating the same task endlessly in a factory or office.

And the first step toward that horizon is already clear and within reach: a radical reduction in working hours—like the four-day work week that some of us are already implementing in our companies.