There Is a Technology Transforming the World, but It Is Not Artificial Intelligence

Can the Same Technological Shift Explain Trump's Victory and the Feminist Movement?

The original (Spanish) version of this article can be found here.

If love, like everything else, is a matter of words,

approaching your body was creating a language.

—Luis García Montero, Love.

Everything changes so quickly that it's very hard to understand the world in real-time. Sometimes, we magnify the impact of a technology, and later, with time, it becomes comical to realize how much we thought it would change everything. Did anyone really believe LaserDisc was going to go anywhere?

But the opposite can also happen. We get so distracted by the promises of things to come, that when a real transformation is happening right before our eyes, we don’t notice it until the world is turned upside down.

That’s what happened with email, perhaps the technology that has changed the world most in the last 25 years. How much has this simple, ancient protocol—compared to the age of the Internet—transformed our lives? It seemed insignificant when we first encountered it.

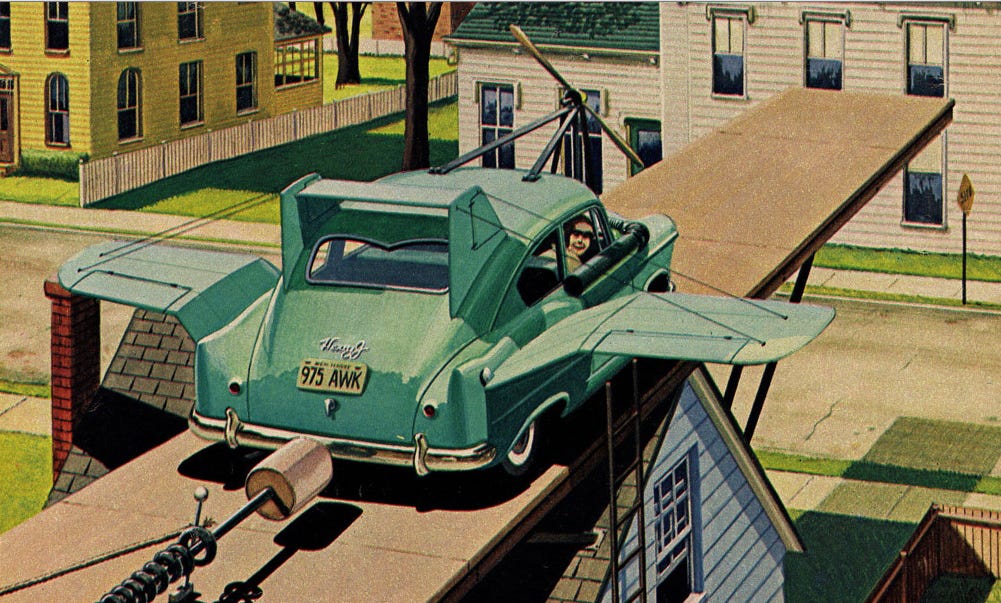

Today, we depend on email for everything. It’s not only changed the way we relate to the world; it’s the closest thing to a digital home we have (also because of all the stuff it stores!). And it did all of this quietly, while the headlines of newspapers announced the arrival of flying cars and household robots.

I believe something similar—and likely much more important—is happening today with another technology. And I believe it is the root of many seemingly disconnected phenomena that we don’t fully understand, like the success of Donald Trump or the feminist movement.

You see, I’ve argued in other articles that human thought is not verbal, but emotional. I’m not just talking about what we typically call emotions, such as sadness, nostalgia, or anger; I’m going further. What we call "ideas" are also emotions. The concept of “home,” or “baby,” or “tax return” are not limited to a word in our consciousness; they activate a set of sensations, memories, and impulses—sometimes smells, tastes, and sounds: they are emotions.

Furthermore, these emotions do not exist autonomously. Unlike words, which are like sealed compartments of cognition, the emotion “home” connects with the emotion “mom” or the emotion “neighborhood” without us fully being able to define the boundaries between them. They cannot be understood separately.

In this way, we can understand the brain as a piano with billions of keys—the neurons—that play different chords. Each chord builds a distinct and complex emotion, interconnected with others. That’s why verbal language, which is much simpler, is not enough—far from it—to transmit all the connections that each of these chords strikes in our consciousness.

For this reason, human existence is a constant struggle to be understood. Connecting with other people—whether it’s with our baby, our partner, or a traffic officer—means making a monumental effort to transmit that symphony of emotions playing in our head with the limited resources we have: verbal language, non-verbal language, physical contact, culture, etc.

And it’s not easy, as anyone who has lived knows. It’s our great drama.

Of course, if it’s hard in person, trying to make that connection without the other person in front of you is even harder. Written text becomes utterly insufficient and doesn’t even begin to transmit what we are feeling or thinking—anyone who has spent several weeks chatting with someone on an app only to realize, when meeting them face-to-face, that the person they imagined is nothing like the one standing before them can attest to this.

But let’s imagine what that effort was like before we even had the possibility of writing. Impossible! Until the advent of the printing press, the vast majority of the population was illiterate. The only way to transmit or preserve ideas was through oral culture: proverbs, songs, the repetition of the same tasks or techniques for cooking, healing, or making tools from one generation to the next.

So, when the printing press began to spread, and with it the ability to communicate complex ideas across distance and time, to connect with people we couldn’t see, that was a revolution so complete, so transformative for the human experience, that the whole world rushed to make the most of it.

Not only was the machinery needed to print books extended, but another, much larger and costlier machinery was built to teach humanity to read and write. Even today, we spend a significant portion of our lives and vast amounts of money on literacy.

If all that effort is necessary, it’s because human language is an extraordinarily complex code. Spanish, for example, has around 100,000 words—plus many more that aren’t in the dictionary—16 verb tenses, 3 moods, and hundreds of grammatical rules (for comparison, a programming language might have 30-40 “words”).

Simply using it correctly requires a tremendous effort, and even that isn’t enough. Using it effectively also requires learning to code those multifaceted emotions through very sophisticated cultural mechanisms. And then decoding them. This act of translating emotional thought into language is what we call “rational thought,” and in society, we reserve some very special places for those who do it best: we call them poets. Or statesmen.

With the ability to communicate across distances also came mass communication. One was no longer limited to the number of people who could hear them; these messages, which some had learned to craft with such excellence, could now reach many people at the same time. That’s why, since the spread of the printing press, mastery of written language became a vehicle of power. Knowing how to read and write well, knowing how to persuade or seduce through text, became an extraordinarily rare and valuable skill. And it still is.

Over the years, a small group of people, experts in reading and writing, came to dominate the pages of newspapers, official bulletins, diplomacy, public administration, universities, and politics. What’s more, because those who excel in this field generally surround themselves with others who think the same way and share that same skill, until very recently it was impossible to be part of an elite without being inside that group of people who were experts in reading and writing.

Until recently, the internet continued this status quo. At first, the web resembled a newsstand, and the same people who had dominated the world through newspapers could continue dominating through a digital version of the same thing. With Facebook and the first blogs, the possibility emerged for everyone to have their little corner and be a small media outlet, but it was still written. The world still belonged to those who knew how to write and enjoyed writing.

But that world is dying. In recent years, a phenomenon has been unfolding right before our eyes, one that is disrupting the last 300 years of written text dominance: some applications are introducing a new mode of communication that hides a transformation that will be discussed in history books. Though it’s not the first, the most important one is TikTok.

TikTok is one of the first social networks native to mobile phones; it didn’t exist before smartphones. From that place, it incorporates two mechanisms that hadn’t existed before.

On one hand, the first-person video, where someone speaks directly to you, without a set, camera, director, or the semantic rules of television and cinema, is the closest we’ve ever come to a face-to-face conversation in history.

Because it’s also consumed in the first person, looking closely at the phone’s screen, it successfully replicates that feeling of talking to someone face-to-face. In this way, the communication codes used in TikTok are the same as those of interpersonal communication: they are those of that much richer and more complex emotional communication than written text.

On the other hand, while on Twitter or Facebook the application has to wait for the user to tell it whether or not they like a piece of content with a conscious and rational act (like clicking “like,” bookmarking, or retweeting), TikTok connects with emotional thought through the unconscious gestures of the user’s hands (how many seconds they watch a video, how many times they watch it, at what second they stop watching, etc.).

With these two seemingly small and trivial innovations—just like with email—the first protocol of communication over distance has been born, one that is not limited to rational thought; it reproduces emotional communication both in the emission of messages and in their interpretation.

Thus, a new field for human interaction is opening up. TikTok is to emotional communication what the printing press was to written communication.

For the first time, mass communication can bypass rational thought and written text and go directly to emotional thought. We are witnessing the birth of the possibility of transmitting ideas across time and space, regardless of the sender’s ability to write.

Like earthquakes, which are felt long before anyone can identify their causes, in these years we are feeling the aftershock of this phenomenon. Everywhere, we see new subjectivities emerging, new groups that self-determine and begin communicating beyond traditional media.

The rise of the feminist movement cannot be understood without this phenomenon. The written word had been a reserve and a reflection of a way of thinking traditionally associated with male thought, with the way men were educated.

Nor can the triumph of Trump and other so-called “populist” parties be understood without this transformation. In the 21st century, the person who succeeds in communication is no longer the one who writes best, but the one who connects emotionally and understands the emotional feedback they receive from their audience.

As a result, there is a shift happening in the structure of power in society, where suddenly those who are capable of connecting directly on that emotional level have the advantage. Meanwhile, the old scribes lose weight and communication power with each passing minute.

That’s why TikTok is filled with videos that, from the perspective of those who have designed their thinking around written text, seem like nonsense. Nothing could be further from the truth: they are loaded with other very complex cultural, social, and emotional codes. The thing is, like written text, if you don’t have certain skills and a lot of practice, it’s not so easy to understand!

It’s very likely that you’re one of those people who, like me, has invested a lot of time, resources, and effort into mastering rational language and written text. And it’s very likely that all this frustrates you, because in this transformation, some will win and others will lose.

You might think that in those apps there’s nothing but people doing dances. But behind those dances, there’s an army of people learning how to communicate face-to-face, using a complex code, difficult to decipher, but also very powerful: they’re inventing a language.

So, if you have any interest in remaining relevant in society 10 years from now, you need to understand how this new form of communication works. You can’t avoid this; you can’t keep looking the other way because it’s not going away, and you’re going to feel more frustrated as time goes on. And if you want your kids to do well in life, they need to learn to make videos just as they’re learning to write.

I know this might horrify you, and you’ve probably heard a million terrible stories about how addictive these apps are. Here’s another way to look at it: they’re addictive because they connect with our brains much better than written text. And the reason for this is that they connect much better with emotional thought.

Unfortunately, the TikTok sphere in Spanish isn’t as abundant as in English. But it’s also an opportunity to create new things, and it’s important that more people—those who never thought they’d have a profile—start running to make one.

So today, I propose that you give this new form of communication a chance, and if it still doesn’t convince you, feel free to scold me here with complete confidence. ;-)