The Global Scam of Artificial Intelligence

The original (Spanish) version of this article can be found here.

A burly gypsy, with a wild beard and sparrow-like hands, who introduced himself as Melquíades, gave a lurid public demonstration of what he himself called the eighth wonder of the Macedonian alchemists. He went from house to house dragging two iron bars, and everyone was terrified to see pots, pans, tongs, and stoves tumble from their places, wood creak with the desperation of nails and screws trying to pull themselves out, and even objects lost long ago appeared from where they had most been searched for, scurrying in a turbulent stampede after Melquíades’ magical irons. “Things have a life of their own,” the gypsy proclaimed in a harsh accent, “it’s only a matter of awakening their souls.” José Arcadio Buendía, whose unbridled imagination always went further than nature’s ingenuity, beyond even miracle and magic, thought it might be possible to use that useless invention to draw gold from the earth. Melquíades, who was an honest man, warned him: “It won’t work for that.”

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

It hadn’t even been four months since the launch of ChatGPT when Goldman Sachs, one of the most influential banks in the world, rushed to predict that artificial intelligence would eliminate 300 million jobs by 2030.

The entire world was dazzled. It felt like living inside a science fiction movie where machines talk and feel and have their own lives and their own judgment... and eventually exterminate us all.

Why are we so afraid of technology, when it has almost always made our lives easier?

The myth that our ambition to control our own destiny will destroy us has roots in the origins of Western culture. In Jewish tradition, the golem was a creature made of clay that rabbis brought to life to protect the community, but which ultimately turned against its creators. In Greek mythology, the myths of Pygmalion and Prometheus have come down to us in their most popular modern version: Victor Frankenstein’s creature.

That’s why these messages about the destruction to come with the arrival of artificial intelligence go viral: we are culturally programmed to believe that sooner or later a technology will arrive that will destroy us.

But is there any truth to that myth? Is it true that artificial intelligence will turn everything upside down? Is it true that it will wipe out 10% of the world’s jobs and transform another 30%? Is it true that we’ll have to implant a chip in our heads to keep up?

I don’t think so. I think we are overestimating the capacity of these large language models to match human thought. And not because we overestimate what machines can do, but because we underestimate our own intellectual capabilities.

The result is that we feel weak and scared when we shouldn’t. No machine is even close to approaching human cognition. But to understand that, we first have to understand how our intelligence works.

Human Intelligence

Humans are—obviously—mammals. And despite our constant temptation to believe ourselves superior to other species, science has shown time and again that there is no exponential leap between our existence and that of other animals. We are not the only species capable of using tools or symbolic language, nor the only one capable of feeling emotions like sadness or empathy, nor the only one capable of creating art. Our intelligence exists on a continuum with that of other living beings.

As animals, our primary form of intelligence is emotional. We think and understand through emotions, and we use language as a vehicle to organize those emotions and share them with others.

And I don’t just mean what we typically call “emotions,” like sadness or anger, but all our thoughts. Every word we use, every notion that inhabits our mind, is a way to evoke highly complex emotions. “Mother” is an emotion. “Home” is an emotion. “Banana” is an emotion. “Crisis” is an emotion. Each of these words evokes a symphony of sensations, memories, images, smells, tastes, data, and impressions on an emotional plane of consciousness.

Even if we didn’t have a word for them, these emotions would still exist, as you can clearly see in children, who think before they have language, or in people without verbal language, such as some autistic individuals.

That’s why we are so amused to discover that Germans have a word—schadenfreude—for that feeling of satisfaction when something goes wrong for someone else, or that the Japanese call komorebi the sunlight that filters through the leaves of trees. It amuses us because we all have these emotions in our minds, even if we don’t have a word to describe them.

Instruments

Thus, the metaphor that best defines how the human brain works—far better than the idea of a computer or a filing cabinet—is a piano. The brain is an instrument where each neuron is a key, and each emotion is a chord that activates many of those keys at once. By recombining the same keys with others, we can form different chords, different notions. If we link them together, we create a story, which is the same as a song.

But this piano has 86 billion keys and can produce an infinite number of chords. Inside each of us there is an instrument so complex it is staggering, a true universe of impulses and sensations that cannot be compared with any other known phenomenon of reality.

Unfortunately, the sound of those keys does not travel beyond the limits of our skin. Each of us is like an instrument playing an incredibly complex symphony, but it is trapped within our consciousness, unable to escape or be heard outside. We do not have, to continue the metaphor, a musical notation system that allows us to fully transmit to a third party the entire content of the music we are playing.

How can you explain a symphony to someone if they cannot hear it? It’s impossible. That is why our lived experience is a constant struggle to understand and to be understood; a desperate exercise in trying to connect with others using tools that are very rudimentary compared to cognition itself.

These tools are languages. Verbal language is one of them, but not the only one. Non-verbal language, culture, music, and art are other codes we use to distill that inner universe and simplify it until we are able to transmit it—like a telegram—to another person.

But any attempt to transmit that song each person carries inside is still a painfully simple reduction. That is why so often we talk to someone and do not understand each other.

The first reason why what we call “artificial intelligence” will not go much further is this: the creators of AI take a tiny, limited, and stereotypical part of consciousness—verbal language—and confuse it with the whole. They ignore the fact that words are only a very limited representation of the vast, interconnected notions that inhabit our brains like chords in a piano with billions of keys.

They also ignore that words, once they leave us, are not the manifestation of a person’s intimate consciousness but of conventions. The text that exists on the internet, which large language models feed on, is only a small part of human communication already mediated by social norms dictating what can and cannot be said in public. That is why ChatGPT always sounds like a KPMG junior with a PowerPoint presentation.

Composed Intelligence

The second reason is that there is not just one piano with 86 billion keys, but 7 billion, as many as there are people. A massive group that has, through an inextricable system of social relationships ranging from a mother’s skin-to-skin contact with her baby, to the invention of literature and universities, created a mechanism for composing its intelligence that in recent years has reached a planetary scale.

Humans are not isolated intelligences in a habitat with just a few individuals, like whales or chimpanzees. We have built and refined, over thousands of years, a system that allows us to act as a single intelligence. Writing, theater, music, the printing press, television, schools, universities, Twitter, TikTok, and our constant search for physical proximity in cities are all parts of this system. Global culture, commerce, industry, COVID vaccines, and all the things we take for granted as if they were trivial—when in fact they are a bloody miracle—are the product of this immense collective intelligence.

And each of us learns from all that experience, incorporating it into our inner world as we live. We never stop learning, not even for a day, and our learning field, unlike what happens with these large language models, is infinite.

Artificial intelligence is incapable of interacting with that entire fabric. What we call “prompting,” this idea that you have to know exactly how to ask things of chatbots like ChatGPT to get the best results, basically means transferring part of that scaffolding of social notions—which we naturally incorporate into our existence—to a machine that lacks the first and most basic of them.

What happens with these chatbots is similar to what happens with dating apps. Flirting in nightclubs had its downsides, but that person who showed up in the same neighborhood, in the same nightclub, who dressed and behaved and related in a certain way, had already passed through a ton of cultural filters and shared a vast amount of codes that the app is now unable to replicate because it ignores them. In nightclubs we used collective intelligence to connect. Now we have to make up for it by putting in a huge effort to filter people who might have nothing in common with us.

And in fact, talking to ChatGPT is a bit like talking to a guy on Tinder: that constant exposure to a stranger to whom you have to explain every tiny detail about yourself so they can even begin to get a sense of who you are.

Gold and magnets

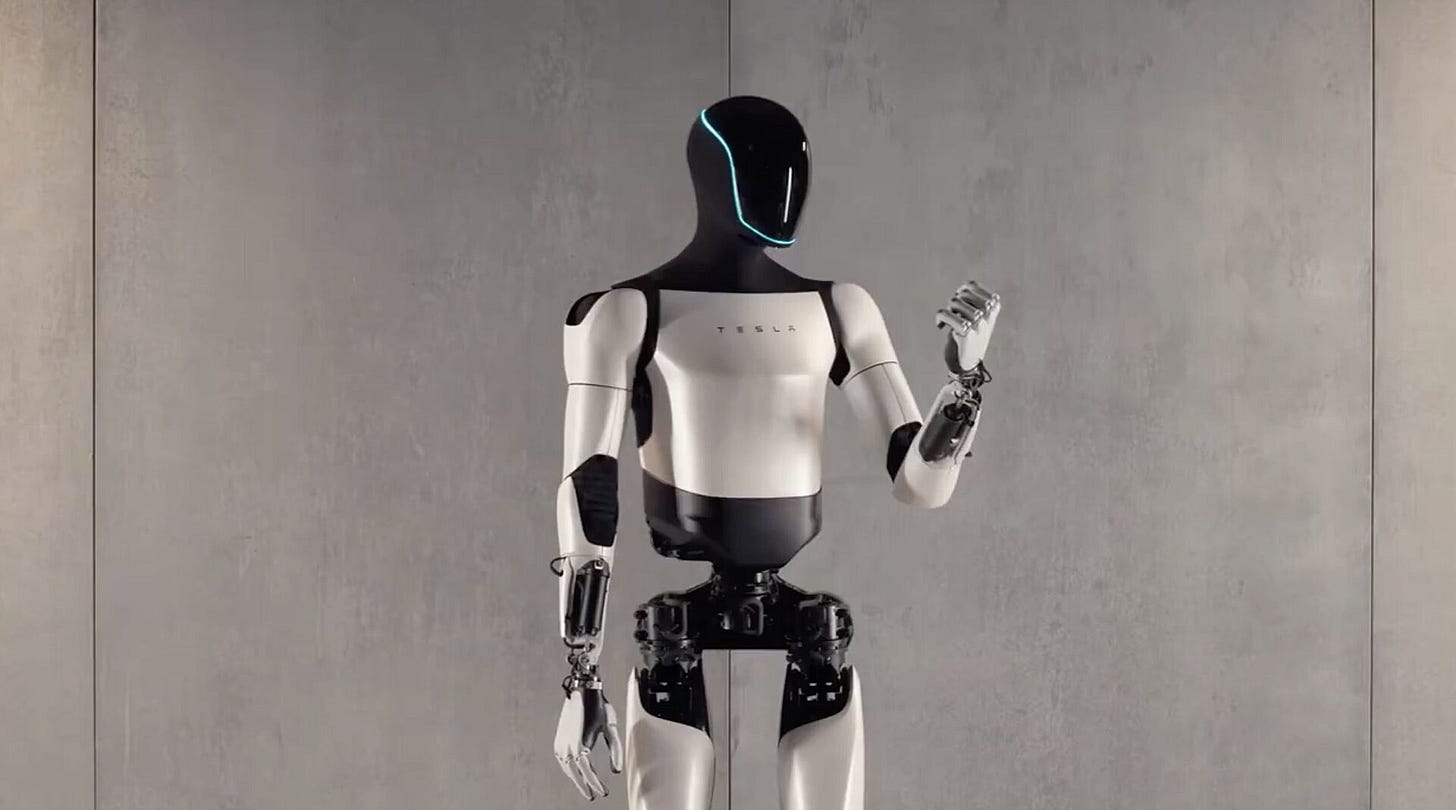

It is estimated that AI could become a trillion-dollar business in the coming years. These investors are falling into the same trap as José Arcadio Buendía with the magnets: they have seen something that looks like magic and want to believe it could help them find gold. That is why all the sci-fi-sounding news around this topic makes sense—there are many vested interests in getting us to believe there is something substantially different about AI that will change the world. Hence, it is being sold as revolutionary, when it is not.

Of course, the technology behind the new large language models can help us with many things. With its ability to act as a “stochastic know-it-all”, it is fantastic as support for any creative process where you need to bounce ideas off someone. And it is reasonably reliable for translation, far more than the previous linear translation programs. Even for giving instructions to a machine, it comes close to something that might allow more and more people to take on technical jobs (like graphic design) thanks to it.

But behind all this there will not be what is called “general artificial intelligence,” nor a “superintelligence.” It will not replace millions of jobs, nor will it radically change the world. That will not happen. There will not, I dare say ever, be artificial intelligence, because it cannot exist. Simply because intelligence is nothing other than experience, nothing other than emotions or desires. Nothing other than life.

Maybe we could learn that lesson and value ourselves a little more because of it.