Housing and the New Feudalism

The more expensive housing becomes, the fewer good jobs there will be.

The original (Spanish) version of this post can be found here.

For weeks, I’ve been going on about a theory to many friends—one that I had been mulling over for years but hadn't dared to put into writing until now.

The idea, put simply, is that the economy has completely changed over the past 20 years, but we don’t see it because we’re still trapped in the 20th-century narrative. This mismatch between what’s actually happening and how we talk about it is responsible for much of today’s societal discontent… and for the confusion among progressive movements. Understanding what’s happening could help us change course and find a vision of a good life for the majority of people, something we currently, quite frankly, don’t have.

Even in 2024, we still imagine the economy as a system composed of three elements:

a) Companies that produce goods and services,

b) Workers who provide their labor to these companies and are compensated for it, and

c) Customers who perceive value in these goods and purchase them.

This was the economy of the 20th century, and it was reflected in consumption patterns:

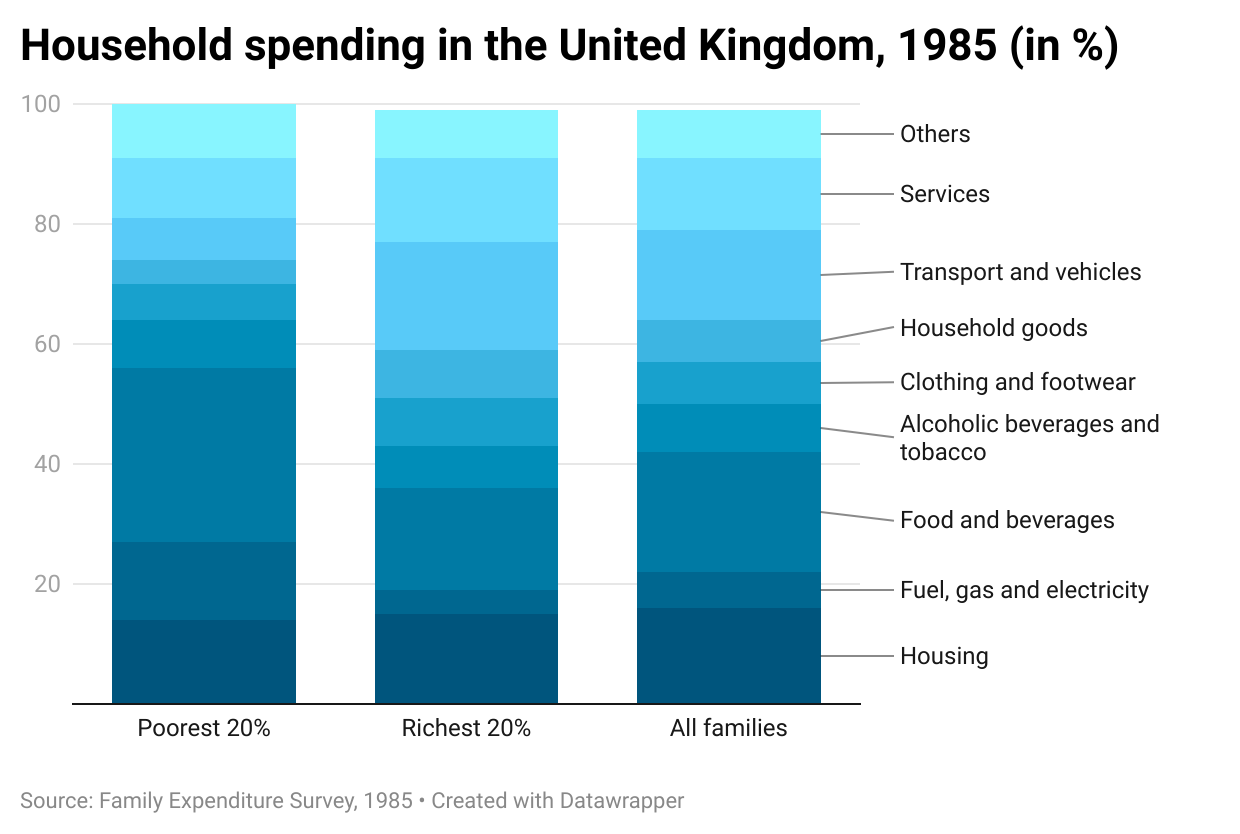

A British family in 1985 spent about 15% of their income on housing and 85% on food, cars, appliances, clothing, and footwear—things that were produced within this productive economy, where good jobs, good wages, and a place in society were available to the vast majority. The father of the family who bought a house in Sussex in 1985 worked in a factory that made sofas. This is the story we’ve heard time and again, the one we still seem to want to return to, and one that, in 1985, appeared to match reality.

But what’s happening now?

Now, the average British family spends 30% of their income on housing and much less on all the things produced in the productive economy.

In Spain, it’s very difficult to find statistics of the same quality, but the ones available tell a very similar story. In 1995, families spent about 15% of their income on housing, while today it’s 30%.

Seems like a price issue, right? Housing is now twice as expensive as before. Tough, but if you tighten your belt and don’t spend it all on drinks, you manage. Then you get the upside of owning a home that appreciates rapidly, and then another, and another. That’s still the prevailing narrative.

But these figures don’t fully explain what’s happening. We need two more data points to understand how much more those born in 1985 are spending on housing compared to those born in 1960.

The first is how long those percentages are sustained. In 1985, a large part of the population paid off their homes in 15 years and bought shortly after leaving their parents’ home (in fact, until the 1980s, this was true for 7% of people). Today, many people rent and save for decades to, at best, get a 30-year mortgage. So, if we don’t just consider the snapshot of annual household spending but the total lifetime cost, someone born in 1960 likely spent less than 8% of their lifetime earnings on their first home, while a millennial is set to spend about 40% of theirs. Five times more. But that’s not the whole story.

The second point is that in 1985, about 35% of women in Spain were working, while today it's over 70% (and this is skewed because among women over 55, workforce participation is still much lower).

So a 20th-century family dedicated half of its productive hours (the man’s) to work, while women’s time covered other household needs. With 8% of a man’s working life, a home was paid for.

If instead of measuring the cost of housing just in money, we consider the effort a family had to make, we see that in 1985, 4% of a household’s lifetime resources paid for a home. Today, we spend 40% of a household’s resources—the working hours of both parents—to put a roof over our heads.

That’s the figure that illustrates this transformation: today, we dedicate 10 times more effort to paying for (the first and only) home than the previous generation. Of the 40 years of our working lives, 16 go entirely to this. From both parents.

There are two massive elephants in the room stemming from this change.

The first is that housing doesn’t generate good jobs, good wages, a place in society, or anything. Aside from the small portion related to construction compared to the number of times a property can be resold, the rest of today’s spending on housing is pure speculation that only fills the pockets of unproductive investors.

Let me repeat that, just in case it wasn’t clear: 40% of all lifetime income for young people is going into a purely speculative economy that produces no value.

Meanwhile, the economy capable of producing good jobs for everyone is shrinking, because we’re spending everything on an unproductive economy, encouraging some to save and invest even more. Every euro spent on housing is a euro not spent in the productive economy. The more expensive housing becomes, the fewer good jobs exist.

The second major issue is that all the surplus that people who aged into adulthood in the 20th century accumulated from their working lives, they invested in one property, then another, and another. We’ve built a vast scaffold where everyone has invested their savings in real estate capital and is expecting a return.

Don’t take my word for it—a damning report by McKinsey on global wealth says it:

“Net wealth has tripled since 2000, but the increase mainly reflects valuation gains in real assets, especially real estate, rather than investments in productive assets that drive our economies.”

Wealth has tripled, but only because of rising real estate values—not from value creation. It’s just more and more people reinvesting profits from one property into the next.

And where does that return come from?

From those who still don’t own homes: either because they pay rent or because they buy properties at 5, 8, or even 10 times what the original owners paid.

Thus, since 2000, the economy is turning into a vast feudal system that creates less and less value but collects monthly rent from a swarm of modern-day serfs who, instead of tilling the land to eat, serve tables in restaurants or create content for social media. But everything else is the same.

Meanwhile, many young people are running like mice in a hamster wheel. They see that there’s a better life on the other side of homeownership, they see the mirage of the 20th-century narrative, and they keep running, hoping to reach the other side.

But there’s no real possibility of that happening. The good life our parents lived was only possible because between 1981 and 2007, 30% of all housing in the country was built. And it was sold for next to nothing, with every bit of available land developed, pumping money into the global system at insane levels, and with 15% tax deductions that likely cost more than all university investment in the same period. The years before the 2008 crisis, with 700,000 homes completed annually, depleted one of the country’s most valuable common goods: urban land.

No rise in the minimum wage can offset housing appreciating 10% annually, as it has in Madrid over the past 25 years. Meanwhile, all these trends continue to worsen with the entrance of professional investors who push prices even higher and remove homes from the market to turn them into hotel assets.

There’s no going back.

A progressive political agenda must stop looking the other way and face the plundering of generations that didn’t buy before 2007—whether through rental prices or by buying properties that cost many times what the original buyers paid. The generational gap isn’t about pensions; it’s about how a country’s capital is distributed.

The alternative leads to a broken world, where part of the population still lives as if we were in the late 20th-century economy, clinging to the dream of a property-owning democracy, with secure jobs and good conditions—while the other half literally gives their lives as the source of returns for the first.

The economy is increasingly made up of just three things:

a) Owners renting (or selling, it makes no difference) homes,

b) Young people paying outrageous rent or mortgages until their last breath, competing in a Hunger Games-style productive economy that keeps shrinking.

If you’re interested in this idea, I have a much longer text on the subject. It’s not finished yet, so I’m not publishing it, but if you write to me, I’ll send it to you.