Donald Trump and the Wars of the Little Scandal

The board on which we build public debate has changed, but we have yet to fully understand it.

The original (Spanish) version of this article can be found here.

Come gather 'round people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You'll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you is worth savin'

And you better start swimmin'

Or you'll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin'

Bob Dylan, The Times, They Are A-Changing.

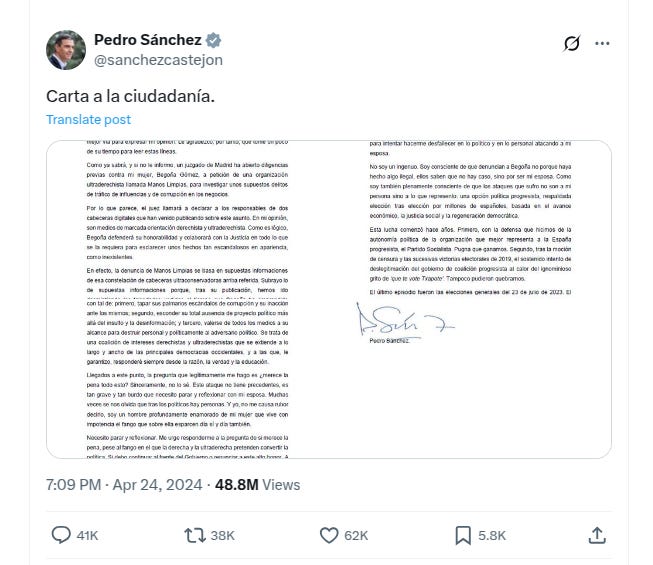

These days mark one year since Pedro Sánchez, Spain’s prime minister, surprised the country by announcing that he would take five days to reflect on whether to continue in office. His wife had just been accused of a crime in a process he considered a witch hunt that had gone too far, and he said he needed time to think about whether it was “worth it” to remain in office despite the ferocious attacks he was suffering.

At the time, I wrote a thread on Twitter that went viral at lightning speed, racking up millions of views and being picked up by radio shows, TV programs, and print media alike (it can also be read on Bluesky, and in video on TikTok). I recommend reading it, because I think it is still relevant today. But above all, I want to take advantage of this anniversary to deepen that reflection and connect it with everything that is happening in the United States. I believe that the same phenomenon that explains Sánchez’s maneuver is the best explanation for Donald Trump’s behavior.

I think the playing field on which we build debate, information, and public consensus has changed — but we haven’t finished understanding it. Everything comes down to the way we perceive time:

Physicists say that time does not exist, at least not as a universal constant. It has no beginning, no end, no fixed boundaries. It cannot truly be measured, except from the perspective of a single person. Time is not a property of the universe, but rather the particular way in which humans perceive reality. For this reason, it changes across eras and cultures, and there have been, throughout history, different ways of understanding it.

In agrarian societies, time was not linear, but circular: determined by the rhythm of the harvests. Reality was not going anywhere; instead, it turned over and over upon itself. That cyclical conception is still alive today in cultures that maintain a belief in reincarnation.

The ancient Greeks also did not have a concept of the future as we know it. Why would they, if the world barely changed over the centuries? For them, time did not advance, and if there was something to project toward, something ahead of them, it was the past, which was where the important things were — like the gods.

The notion that time is linear, and that people advance through life toward a future, did not become widespread until the spread of the Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam). But even then, the future was not in earthly life; rather, earthly life was a transition toward the true destination: eternal life after death.

Between the 18th and 20th centuries, another belief took hold, the one that has carried us through to the present. Riding on the idea that technical and scientific progress would indefinitely improve people’s lives, the vision of a mythical, idyllic future was born — a future full of technology and technical marvels that would change our lives forever. It was the era in which World’s Fairs showed off what was coming, and what was coming was always better than the present. As a consequence, people began to project themselves toward that future, even at the cost of their present.

And it made perfect sense. If the future was going to be brilliant, but the present was not yet there, the best decision was to save all resources in order to fully enjoy them when the time came.

The foundations of our current society stem from this belief. Saving, for example, is a way of prioritizing the future over the present: we sacrifice our current consumption to make a purchase later on. Diets work the same way, privileging our future well-being over immediate pleasure. Effort — the cornerstone on which our entire moral system still rests — is exactly this: the idea that it is worth going through difficulties today in exchange for a reward tomorrow. Even credit, investment, and debt follow the same logic; they are the same phenomenon of saving and effort, taken to the economic level.

But what if the idea of the future were to disappear again? What would reality look like if time stopped being linear and forward-oriented?

Much of the confusion we feel today stems from the fact that we are abandoning the way we understood reality in the twentieth century, and a new one is emerging.

First of all, because the belief that guided the 19th and 20th centuries — that the future would be a wonderful place — is crumbling. We have arrived in 2025, the year that was supposed to be “the future,” and that utopia of flying cars, household-cleaning robots, and Martian colonies is nowhere to be seen. Quite the opposite: people have stopped believing that the future will be better than the present, and they no longer want to think about it. The futuristic movies and the collective dreams of an advanced society are gone. As Peter Thiel says, “We wanted flying cars, but instead we got 140 characters.”

This, and nothing else, is the reason why young people save less than their parents did. Far from living a capricious lifestyle, young people are making a very rational choice: they think their future will be darker than their present, and they prefer to materialize their investments today. This trend has only accelerated since the pandemic made us believe that our reality was much more fragile than we thought.

So we have gone from a world oriented toward the future to a world that no longer knows where to look for a hopeful image. And while we were distracted trying to figure out where to look, something else happened:

The internet has been in our lives for so long that it has changed the way we understand reality. Before the web, one could look at the world as a more or less static place, like a photograph in which everything stayed in the same place. This way, we had an unchanging image of the past, another image of a promising, but also static, future, and a present that moved so slowly it could be understood as an almost stationary reality.

But if we superimpose one photograph on top of another and another and another, and pass through them very quickly — which is what social media does — we produce the impression of movement.

Thus, we have gone from a static world to one in permanent motion. From life as a map of known places to life as a stream of events happening at breakneck speed, beyond our ability to fully comprehend.

And the problem is that we still do not know how to swim in that stream. That is why so many people feel they have lost control, even of their own attention and their ability to concentrate. Overwhelmed by a flood of stimuli they cannot grasp at such speed, many people feel they have lost control, that they have lost the capacity to intervene in their own lives — that this current is sweeping them away.

The most human reaction to that sense of lost control is to try to recover it. It is an instinctive reaction to the unknown, just as when we hear a loud noise or spot a stranger in a parking garage. Our senses immediately go on high alert to try to understand what is happening again. That is why we keep coming back, over and over, to social networks, to connection with others, paying frantic attention to everything that is happening, in search of answers that might help us get our footing again. That is why, if we disconnect, we feel that we understand less and less — and to a large extent, that is true.

The World Wars of the Little Scandal

In this state of permanent alert in which all human beings live in the third millennium, the tools we had built to understand the world — politics, philosophy, and the media — have become obsolete.

As products of the 20th century, they persist in that venerable but useless effort of asking what the world should look like in 100 years. Parliamentary politics, with its debates, its nineteenth-century codes, its laws that take years to materialize and five-year plans to produce results, with its grand blueprints for making the world a better place — but never today — have been relegated to the very last place when faced with the need to understand what is happening exactly this very week, and which could blow up the world before the next one begins.

The media, which continue to devote an illogical amount of time to acting as an echo chamber for all those debates, do not help either.

And in a world without leadership, each person looks for a mast to tie themselves to, something that can give them a sense of security amid this storm: something that explains what is happening and tells them what to do to feel safe.

And the shortest path to feeling safe is feeling important.

That is when certain people emerge who know how to play this game. They understand, like Pedro Sánchez, that the key to the contemporary world is not leading people toward a distant future, but constantly explaining today’s reality to them. “Framing the narrative,” as political scientists would say, but not with a grand plan — with a plan every single day.

That is why the metaphor that politics has stopped being a chess match and has turned into a basketball game makes sense. We have gone from a rule-based world, where politicians could control the norms and the “turns,” to a complex world with many players and infinite possible plays.

And the important thing on that court is to keep possession of the ball and set your own conditions. And not with a grand, future-oriented strategy, but with a quick strike, then another, and another, and another still.

And that “ball” is attention. Because at a time when we still don’t know how to properly understand and filter all the content we receive daily, the person who frames the narrative is not the best analyst, but the one who best knows how to capture people’s attention.

Donald Trump is a world champion of attention. He has been playing this game all his life. When he was young, he grabbed the front pages of the tabloids with his glamorous girlfriends and his gold-plated million-dollar investments. In the Anglo-Saxon world, he became something like a super-sized Wyoming (translator’s note: a Spanish comedian), when, for 14 seasons, he hosted a prime-time reality show called The Apprentice, but it could have been called Trumpworld: filmed in Trump Tower in New York, starring himself, with the prize being a job… working for him.

Decades spent refining his gestures, his announcements, his megalomaniac projects, his outrageous stunts… and the thousands of ways to provoke in order to grab attention.

These days, all the analysts are trying to decipher what Trump’s real intentions are with tariffs. Is he serious? Or is he just trying to negotiate hard? As Ángel Villarino so wittily put it this week, we have all turned into Trumpologists, each of us with our own school of thought to try to understand what is happening.

This is my own personal school of Trumpology:

Trump is not interested in tariffs or in anything else. He does not want to end the war in Ukraine, nor the opposite; he is not interested in Putin, nor uninterested; he does not want to annex Greenland, nor refuse to annex anything. What he has been doing from the very first minute is the same thing he has done all his life: launching one volley after another at public opinion to get attention and keep it. So that people talk only about him, so that he has permanent possession of the ball at any price.

That is why one day he announces tariffs and, the next day, withdraws them without negotiating anything in return. That is why he releases outrageous videos about building a resort in Gaza and deports Venezuelan citizens to Bukele’s prisons, just to get a shocking image. That is why he is firing federal employees. That is why he proposed naming a special prosecutor to investigate Joe Biden, carrying out the largest mass deportation operation in U.S. history, relocating homeless people to concentration camps, eliminating the Department of Education, imposing 60% tariffs on all Chinese imports, banning — or deporting — immigrants for their ideology, holding military trials for drug traffickers, giving “total immunity” to the police, using the military for domestic security, pardoning the January 6 insurrectionists, building massive migrant detention camps, deploying drones to fight urban crime, and amending the Constitution so he can run for a third term.

Some of these ideas have not been formally withdrawn, but their legal and practical feasibility is widely questioned. It does not matter. Trump’s only objective is “to win the day”: to be the protagonist of the day, to keep possession of the ball.

There is no plan in his head. There is no future in Trump’s mind. He thinks in a completely different way from traditional political strategists. That is why he imposes tariffs without projecting absolutely anything to develop domestic industry. Even the twistedly stupid way of presenting the tariffs was a way to keep us guessing how he calculated them, whether he used AI to do the calculations, whether he included uninhabited islands on the tariff list… all just to keep us talking about him.

I am convinced that in the coming days he will renegotiate the tariffs, just as he already did (twice) with Canada and Mexico. Not as a strategy to achieve better trade conditions, but to win another day on the front pages.

In Trump’s mind, his enemy is not even the Democrats because they do not even compete: his rival is the Super Bowl final and the latest Ed Sheeran album.

When he finishes with the tariff war, he will make something else up. And then another, and another. There will come a time when everyone will figure him out and get bored. It is possible that then he will get nervous and raise the stakes. I seriously worry that in this spiral, he could end up provoking an armed conflict — the ultimate infinite source of attention.

In the meantime, there is something we could learn from what we are experiencing. If the twentieth-century world was obsessed with the future, the twenty-first-century world is obsessed with the present. And leading the world today is not about creating twenty-year projects, but about accompanying people so they feel like protagonists and in control of their own lives today.