DeepSeek and the Mutation of Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is no longer the mecca of innovation; it has become a machine dedicated to producing investment products, regardless of whether those products actually transform anything.

The original (Spanish) version of this article can be found here.

The question one must ask today to understand what is happening is: how is it possible that a Chinese hedge fund managed, in a single year, to steamroll over all the major players competing for supremacy in artificial intelligence? How can its software be cheaper, more efficient, faster, more powerful — and open source, to boot — and no one saw that this could be done until now? Does DeepSeek have something special, or will more competitors like it soon appear?

If it was such an exceptional engineering feat, supposedly out of everyone else’s reach, how could a company whose main activity isn’t even this, and with just a fraction of the funding the others invested, manage to trounce them all?

Here is an answer I don’t think you will have heard anywhere else: the CEO and management of all those other startups were not focused on developing the technology, because the business model of Silicon Valley is no longer to create successful technology.

You see...

It’s a story we’ve heard a million times. In the 1970s, a bunch of hippies armed with a few transistors sparked the connected society revolution. Since then, Silicon Valley has been synonymous with innovation.

Although the internet didn’t begin as a business initiative, in the 1980s and 1990s it was transformed into companies that changed how we live: Apple, Microsoft, Oracle, Intel, Cisco, Sun, and HP. Over time, these companies became giants of the American stock market and massive sources of profit for their shareholders.

With the exception of Microsoft, which sold software licenses, all these companies’ business models were not that different from traditional businesses: they sold physical things, even if they were computers, microchips, or servers.

Later, another generation of companies led by Google marked a fundamental change in business models. Google didn’t sell hardware or software; it offered an online service. At first, it focused on search, but over time expanded its offering. This model had a revolutionary twist: to succeed, it had to serve a massive user base, even if only a small fraction of those users paid for its services.

Unlike HP, whose only customers were those who bought its products, Google had users: everyone who used its tool, regardless of whether they paid or not. This idea was radically different from the traditional model, where companies only cared about paying customers.

Obviously, Google did very well. To replicate that success, the notion spread that in the digital economy, the path to success did not rely exclusively on immediate revenues but on achieving traction: attracting a large user base, even if those users did not initially generate income, and then, once a market was dominated, “monetizing” or converting those users into paying customers.

In the 2010s, another wave of companies like Airbnb, Uber, Facebook, or LinkedIn promised to repeat the same play. This generation of companies was born losing money but managed to convince the world that, in a few years, they would change everything just like Google did — and then reap crazy profits.

Some of these companies delivered on their promises. Others are still losing money 15 years later. Uber made a profit for the first time in 2024, after 15 years of operations. Airbnb in 2023. In any case, their tiny profits do not justify their stock valuations, yet they persist.

The point is that this forever changed Silicon Valley’s business model. Since then, nobody is truly focused on developing innovative technologies with millions of customers and charging for them. The business model of Silicon Valley is about convincing a ton of investors that your startup is going to turn an entire industry upside down, and raising enormous rounds of funding in the meantime.

The task of any CEO in “the Valley” is to generate the expectation that they will change the world — but not today!, because that would force them to quantify the scale and scope of that change — but in a few years. And in the meantime, to keep feeding the company with millions and millions of dollars from investors who expect a profit not because the company will ever turn a profit, but because its valuation will keep rising and its shares will keep going up.

This model has many virtues for many people. One is that it gives engineers and startup founders the chance to embark on crazy — and fun — projects instead of working on the umpteenth version of something that already exists. It is also common for part of the compensation in these companies to come in the form of stock options. In fact, one third of NVIDIA’s employees hold shares in the company.

Another virtue is that the media loves to hear these promises from companies that will change everything. From those promising “a butler for the 99%” to others offering to end supermarkets and deliver groceries to your home or turn your car into an Airbnb-style rental.

The last — and most important — virtue is that this logic offers an extraordinary investment (or speculation, you decide) vehicle at a time when investment opportunities are scarce.

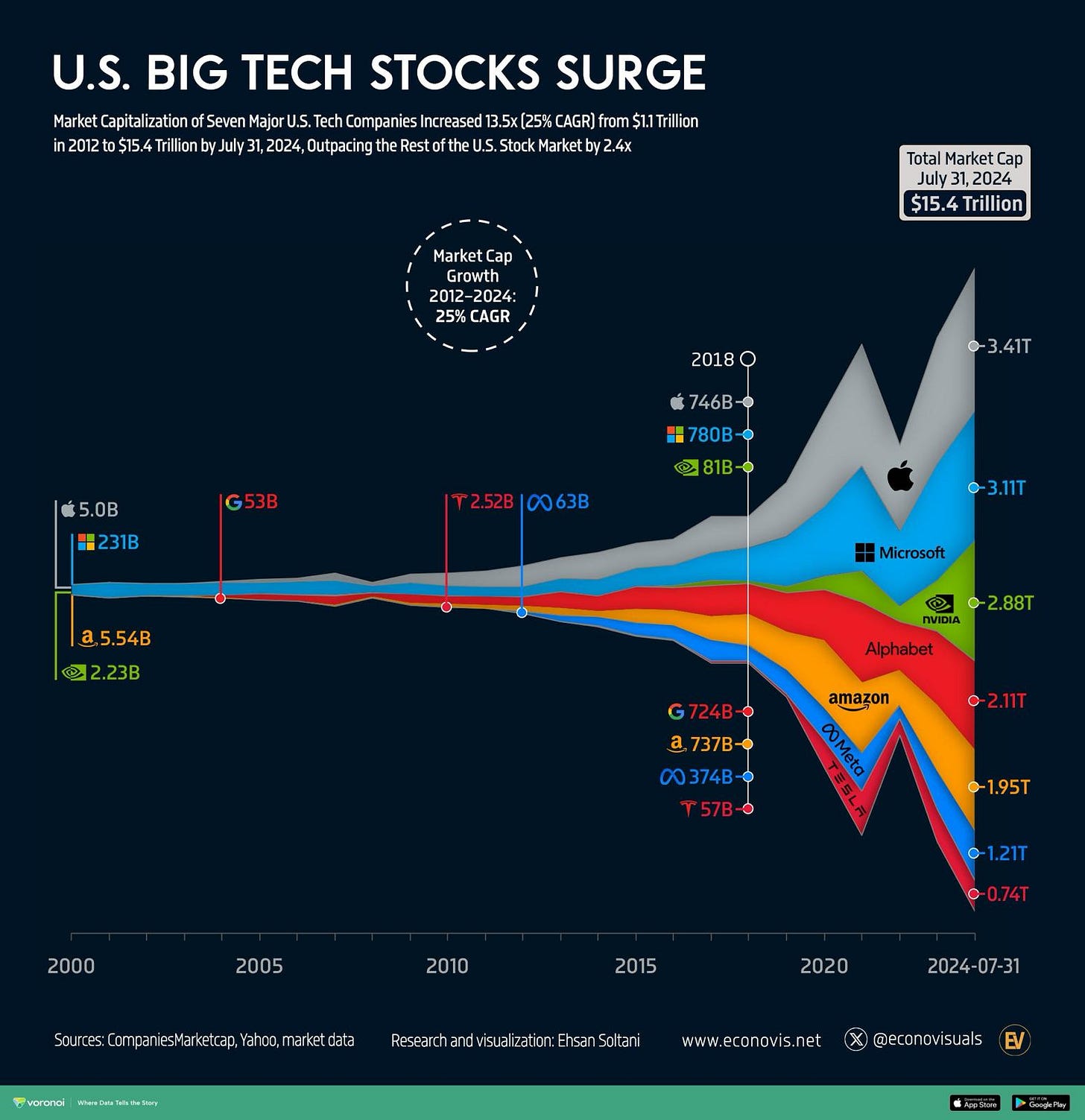

That is why in recent years the share prices of the so-called “Magnificent 7” of the American stock market have skyrocketed (Apple, Google, Amazon, Meta, Nvidia, and Tesla), becoming the perfect investment product with immense unrealized growth expectations.

As a result, the startups that succeed are not those developing the best applications, but those that are most successful in convincing investors. And executive teams spend far more time chasing new investments to keep paying salaries and keeping the company afloat than they do developing the product. They spend more time with the CFO than with the CTO. Their customers are not their users but their investors.

That is why all these companies have spent months fully dedicated to convincing the world they are going to produce something amazing that hasn’t arrived yet, while their applications have not substantially improved since 2022. That is why they have lost sight of the fact that the technology they are working with is nothing exclusive but rather born of collective intelligence and will inevitably become an open-source universe where the only money to be made is in building specific applications for particular uses.

We are seeing something that has already shown up in the poor quality of some Google products in recent years: startups and tech companies that survive on investor money in Silicon Valley are no longer the best structures for producing disruptive technologies. They’re doing something else entirely!

Silicon Valley is no longer the mecca of innovation; it is a machine designed to produce investment products, regardless of whether those products end up transforming anything. And in that sense, it is doing phenomenally well: just in the field of generative AI, they were trying to raise a trillion dollars in investments, until Donald Trump promised another half a trillion from the US government.

The consequence is a huge bubble in the valuation of tech companies that has been building up for 20 years. And it has all the makings of bursting in the coming days.

There is nothing in DeepSeek that cannot — and surely will — be emulated by another team of engineers somewhere else in the world in the coming months and years.

Let’s see how they explain that to the investors...