Data Centers or Houses: Will AI End the Housing Market?

Wherever you look, the story is the same: coinciding with the explosion of AI, housing prices have fallen in almost every major metropolis.

The original (Spanish) version of this article can be found here.

The financial world—or the world of investment, or of capital, call it what you like—is a story in perpetual evolution. Stock markets and assets are nothing more than bets on what things will be worth in the future: pure narrative. To function, to stay in motion, they always need some kind of collective story to sustain them.

It’s no trivial matter. In 2025, that story says that the world’s wealth is six times the value of global GDP—about $620 trillion. Even in private thought, many people pay far more attention to their properties—the value of their house, their savings, or their future inheritance—than to their salary.

Today, two parallel stories are sustaining all that (imaginary?) wealth.

One is that the economy is booming: employment is at historic highs, wages keep rising, the shocks of COVID have given way to a moment of monetary calm, and the imperial ambitions of satrap Vladimir Putin haven’t been able to throw the global economy off course.

Riding this wave of prosperity, the story goes, houses and other real estate assets will keep rising indefinitely.

Investors of all sizes love this story. Real estate is a monopolistic market, where supply is limited by public authorities who are much easier to control than any free market. Most countries protect real estate investors more than any other asset class. And housing is such a basic need that people stop paying for anything else before they stop paying for their home. Investing in housing is like investing in toilet paper—but with a 10% annual return. A bargain.

If you don’t believe it, just look at the data: since the year 2000, virtually all “wealth” has come from the revaluation of real estate assets. In other words, in the last quarter-century, the only form of wealth that has really grown is real estate, which now makes up two-thirds of all global wealth—almost $400 trillion.

The other story driving today’s markets is that so-called “artificial intelligence” is such a powerful technology that it will revolutionize everything. All of society. And that it will boost productivity to levels never before seen. “AI is the new electricity,” as Andrew Ng, founder of Coursera, once said, a phrase that perfectly captures the core of this story.

As a result, there is another fantastic investment opportunity: data centers—huge warehouses filled with computers that rent out their computing power to others. Processor farms.

Here’s the story: unlike previous technologies, AI is extremely intensive in computing capacity. It needs vast numbers of processors to train models and to run inferences. As a consequence, in the race to reach the new AI frontier, up to $7 trillion will need to be invested in these behemoths within five years. That’s about 10 times the size of the EU’s Next Generation funds, to put it in perspective.

If the story of workers paying rent tickled investors’ stomachs, imagine machines paying rent… tenants that never complain about broken heating. Data centers are the fever dream of international investment: the holy grail of guaranteed cash flows.

If you don’t believe it, just look at the data:

In 2025, just Google, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft alone will invest $350 billion in data centers. “AI CAPEX,” as this infrastructure spending is called, has already outpaced American consumer spending in its contribution to U.S. GDP growth this year.

That’s a big deal, because the American economy is famously consumer-driven. The political system and every incentive are designed to keep consumption as the nation’s engine. What’s happening now is unprecedented: this year, AI investment will contribute more to U.S. growth than the increase in consumer spending.

So those are the two stories driving international capital markets today. And they both have one tiny, tiny problem…

If AI is going to revolutionize everything and drive productivity through the roof, it will be by creating the most brutal wave of technological unemployment in history. Some estimates put the figure at up to 300 million jobs. It’s that reduction in labor costs that will fuel the profits eventually ending up in the hands of investors and data center owners.

But if that’s the case, then… who’s going to pay for the houses?

…

…

…

If you’re thinking you haven’t seen this warning anywhere, trust me: the most important trends never show up in newspapers, but in data. And all the data points to international investors having already reached this very conclusion. Since the emergence of ChatGPT in 2022, the mothership of AI, housing prices have been dropping significantly in most of the world’s major cities.

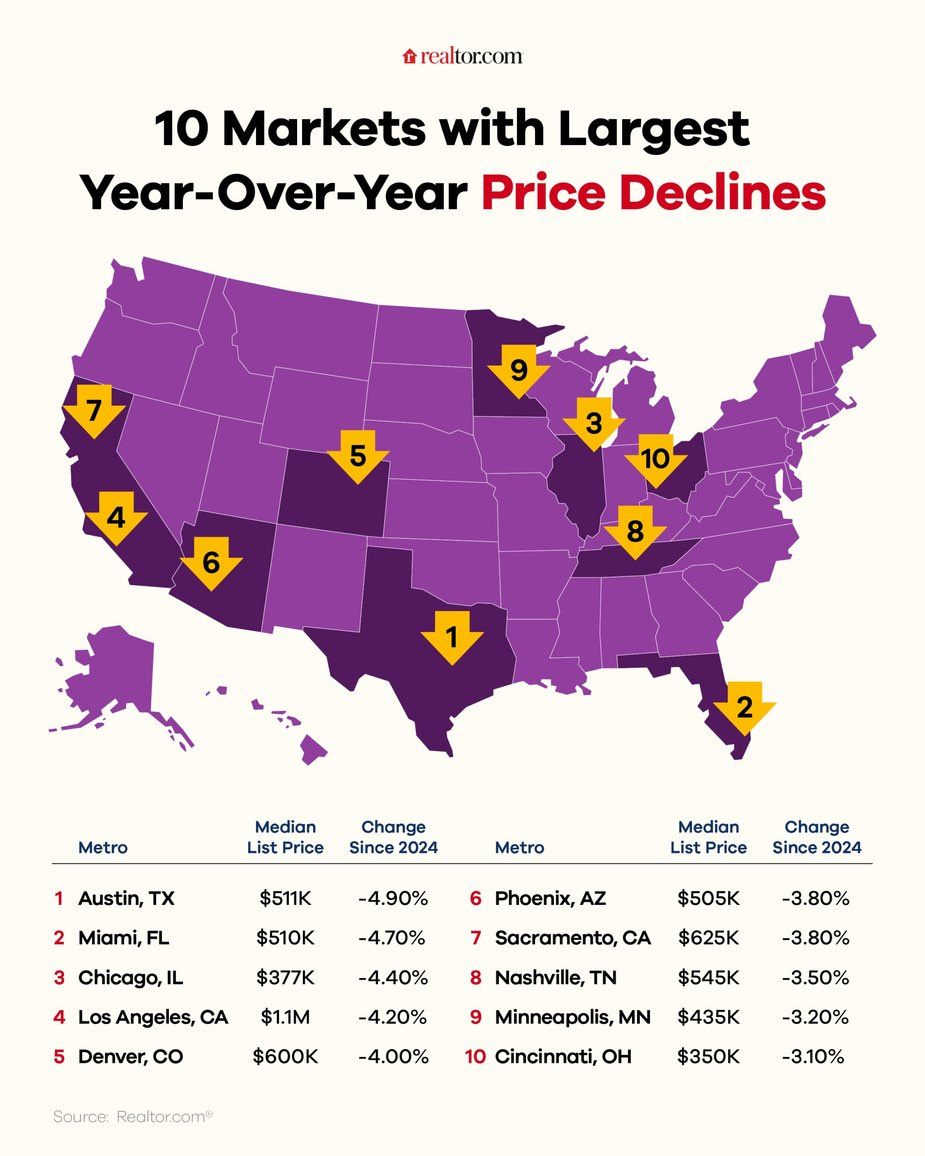

This week, various datasets were released, all pointing in the same direction. In the U.S., home prices have fallen in the past year in 33 of the 50 largest metropolitan areas.

The list includes Los Angeles and San Francisco, Boston, Chicago, Miami, Denver, Phoenix, New Orleans, Las Vegas, and Sacramento, among others.

One striking case is Austin (-8.5% in the year, -15% since 2022), which had been one of the great success stories of American urban economics over the past decade. In just a few years, the city had become a major hub for tech entrepreneurship, to the point that many media outlets dubbed it “the new Silicon Valley”.

It now seems that some of the U.S. economy’s big bets—like Austin, or the mega-bubble Miami had become—are deflating like birthday decorations the morning after.

“A couple of weeks ago I issued a yellow warning light for the housing market,” explained Moody’s chief economist, Mark Zandi, “but now I think it’s more appropriate to turn on a red one. Home sales, construction, and even prices are about to fall unless mortgage rates drop significantly from their current level, near 7%. But that seems unlikely.” Even in Manhattan, prices have dropped this year—3.8% annually.

Across the Atlantic, something similar is happening. London prices suffered in July their steepest fall since records began. Driven by the collapse in the most expensive neighborhoods—where in some cases prices have dropped up to 36% since Brexit—the crown jewel of Europe’s housing market is down 1.5% year-on-year. Kensington and Chelsea, the capital’s two priciest boroughs, are now at 2013 levels.

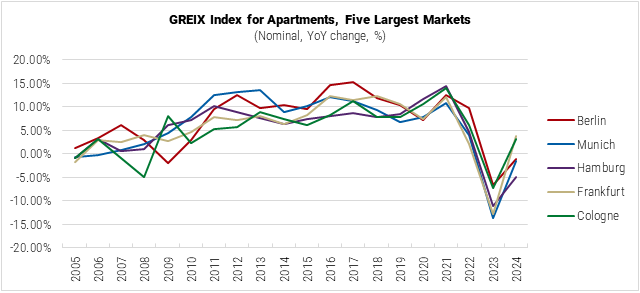

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Europe, prices have fallen in all major German cities, as well as in Stockholm, Paris, Copenhagen, and Helsinki, among many others.

At the national level, prices are flat or declining in Germany, France, Austria, Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. In Spain—where, as we all know, we tend to arrive late to everything, including the news—prices have actually risen 15%, the second-largest increase in the eurozone over the same period.

Wherever you look, the story is the same: since their historic peak in 2022, coinciding with the explosion of AI, housing prices have declined in nearly every major American and European metropolis.

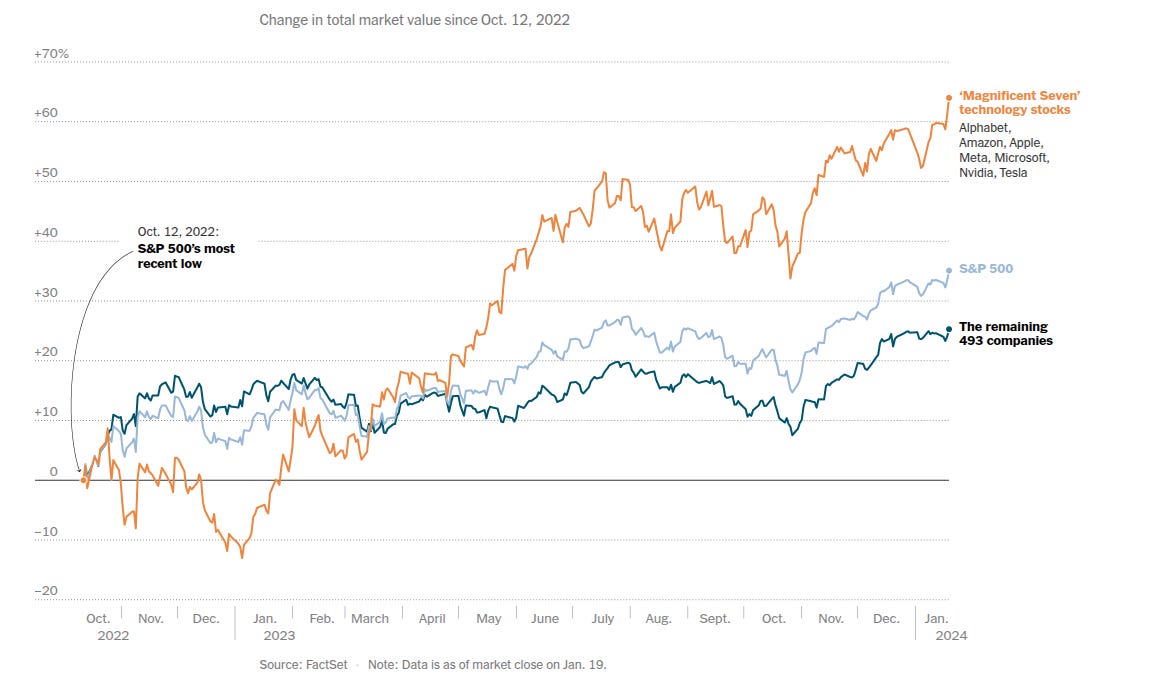

In the same period, the valuation of the “Magnificent Seven” on the U.S. stock market—the companies cashing in on this phenomenon (Apple, Amazon, Google, Meta, Tesla, Nvidia, and Microsoft)—has tripled, rising from $7 trillion to $19 trillion, and from representing 21% of the index to 35%.

One might think investors are leaving (or avoiding) the housing market to enter AI. But that doesn’t make sense. If the profit expectations were as strong as advertised for both sectors, no one would stop investing in one to invest in the other.

The reality, as every fund manager understands, is that in this battle between AI and housing, only one can win.

Or, seen from a broader perspective: we are watching, before our very eyes, the ultimate contradiction of this late stage of capitalism. Its impossible determination to live off consumption while trying at all costs to abolish labor. Firing workers while selling cars, cutting wages while raising rents.

This drama has one last ingredient: it’s a recursive problem. If wages have risen in recent years, it’s because the economy was artificially inflated by the expectation of a technological revolution and by the housing bubble. If those expectations fall, or housing stops rising, there will be no jobs. But if there are no jobs, who will pay for housing? What consumers will buy the products made by AI?

And then they say God doesn’t play dice with the universe. Wouldn’t it be a delicious irony if the technology that was heralded as the great executioner of labor ended up executing capital first?